Larry Doby got what shut-eye he could, as the bus carrying him and his Negro League teammates made its trek from Wilmington, Del., to Newark, NJ, in the early morning hours of Thursday, July 3, 1947.

As Doby slept that night 75 years ago, he did not know about the newspaper report bearing his name. Didn’t know that his home would, in a matter of hours, be swarmed by inquiring reporters. Didn’t know that his life — and the entire structure of professional baseball — was about to be enduringly altered.

By the time Doby disembarked the bus, driven his Ford convertible to his apartment in Paterson, NJ, and gotten into bed for more proper rest, it was roughly 5:30 am. And it was just before 7 am. when Newark Eagles owner Effa Manley rang Doby’s phone and cut short his sleep with the big news.

“Larry,” she said, “you have been bought by the Cleveland Indians of the American League and you are to join the team in Chicago on Sunday.”

While Jackie Robinson’s color-barrier-breaking debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers eleven weeks earlier was a cultural touchstone and a vital precursor to the American civil rights movement, it is important to consider what the purchase of Doby’s contract meant not just for the now-integrated AL but for the very structure of professional baseball.

Robinson, after all, had signed his contract with the Dodgers in October 1945 and spent the entire 1946 season in the Minor Leagues with the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate in Montreal. He was promoted to the Majors six days before the start of the 1947 season, unofficially debuting in an exhibition game at Ebbets Field four days before the real thing.

Doby, on the other hand, arrived at the AL literally overnight, on a Pennsylvania Railroad train.

So something more definitive was communicated by Doby coming to Cleveland. If Jackie was baseball’s experiment with integration or the sewing of a seed, Doby was proof that the seed had taken root. There could be no denying now what was happening and what would happen. The death knell had been sounded — bittersweetly — for the Negro Leagues, with the best Black players plucked and rostered and finally able to display their talents on baseball’s biggest stage.

“The entrance of Negroes into the Majors is not only inevitable,” Cleveland owner Bill Veeck told a reporter when the Doby signing became official, “it is here.”

The desegregated MLB, which should have been in existence all along, was finally going to happen.

And in Larry Doby’s case, it was going to happen fast.

The difference between the respect Doby commanded in Newark and the cold shoulder he received from some in the Cleveland clubhouse — to say nothing of opponents — just 24 hours later could not have been more stark.

When the Cleveland players trotted out to the diamond for pregame warmups, Doby found himself without a catch partner. He stood outside the dugout, humiliated, for mere minutes that felt like an eternity. In that moment, those feelings of loneliness that had pervaded Doby’s youth sprouted up again. But when, at long last, All-Star second baseman Joe Gordon tossed him a ball, Doby encountered his first player ally in his integration.

That afternoon, Cleveland trailed, 5-1, entering the seventh inning, when Doby was summoned with one out and two aboard to pinch-hit for pitcher Bryan Stephens. A crowd of mixed-race cheered his arrival to the plate as he nervously dug in.

“I didn’t hear a sound,” he later recalled. “It was like I was dreaming.”

Doby swung and missed at White Sox pitcher Earl Harrist’s first offering, then fouled off the next. He let the next two pitches pass for balls but swung through the fifth pitch to go down with the K.

“Well,” Boudreau told him upon his return to the dugout, “now you know some of what it is all about. You are now a big leaguer.”

The strikeout was emblematic of Doby’s first partial season in the AL. He appeared in 29 games, made 33 trips to the plate, and hit just .156 (5-for-32) in 1947.

Doby, though, had been raised to endure tough times and harsh changes. Just as he didn’t let his odd upbringing lead him down the wrong path, he didn’t let the strikeouts, the segregated hotels, the “whites only” taxicabs, the insults, the slurs, or the time he was spat on while sliding into second base deter him from his dreams.

In 1948, Doby, blocked at second by Gordon, was tasked by Veeck with moving to center field in order to carve out a regular spot in the lineup. The position change only added to the 24-year-old’s full plate. But the versatility that served Doby well as a four-sport athlete in high school also served him well in the move to the outfield. His bat caught on that year, too. With the help of Doby’s .301 average, 14 homers, 23 doubles and nine triples, Cleveland captured its first AL pennant in 28 years.

And Doby’s 7-for-22 showing in the World Series against the Boston Braves — including what turned out to be the game-winning home run in Game 4 — was instrumental in claiming what still stands as the franchise’s most recent championship crown.

From that point on, there was never again a doubt as to whether Doby could make it in the Majors.

He was selected to the AL All-Star team every year from1949-1955 and finished in the top ten of the MVP voting in 1950 and 1954. After his playing career, he became a scout and a coach before Veeck, who by this point was owner of the White Sox, called upon him again in 1978 by making him MLB’s second Black manager, behind Cleveland’s Frank Robinson three years earlier. As was the case in his AL debut, Doby was thrust into that duty in the middle of the season.

To be second, Doby learned, is to be generally underappreciated and acknowledgment can be a long time in coming. He went 39 years between his final game as a player in 1959 and his rightful induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998 — an honor that came just five years before his death from cancer at age 79.

Doby though, set a template that not even Robinson could claim, for he was the first Negro Leaguer to jump directly into the big leagues. Imagine being cheered lustily one day at a ceremony in your honor and then having a teammate deny you a handshake the very next.

For his part, though, Doby was glad to have had so little time to prepare for the “new and strange world” he penetrated.

“I look at myself as more fortunate than Jack,” he once said of Robinson, with whom he became close. “If I had gone through hell in the Minors, then I’d have to go through it again in the Majors. Once was enough!”

There was only one Lawrence Eugene Doby. No, he was not MLB’s first Black player. No, he does not have a day in which the entire league wears his No. 14, as they do for Jackie and his No. 42 each April. No, he is not the subject of dozens of books or a feature film. And no, he was not saluted as a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

But this much must be said and understood about the man whose legacy is too often neglected: The call came, rousing him from sleep and inviting him to do something he had never been done. And to the benefit of the many who followed in his footsteps, Doby answered. ●

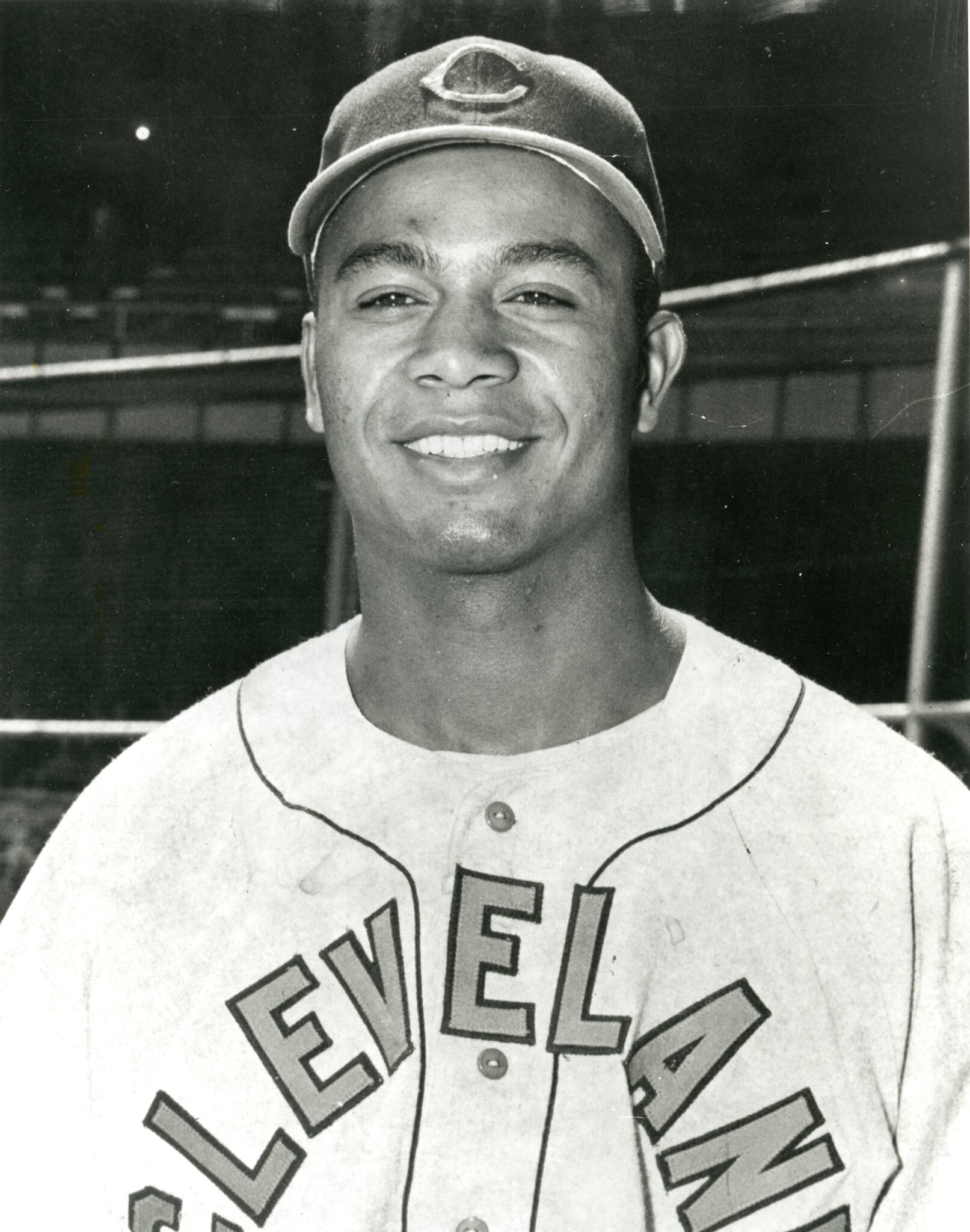

Larry Doby Debut 75th Anniversary Celebration

Saturday, July 2

Yankees vs. Guardians at 6:10 pm

Doby 1947 Jersey, courtesy of Discount Drug Mart (15,000 fans)