Here are the rules if you want to interview a superhero: You must be flexible with your time; you must have an idea of what you want to ask; the questions cannot be boring. Superheroes are always thinking about the next soul to save and don’t have time for mediocrity.

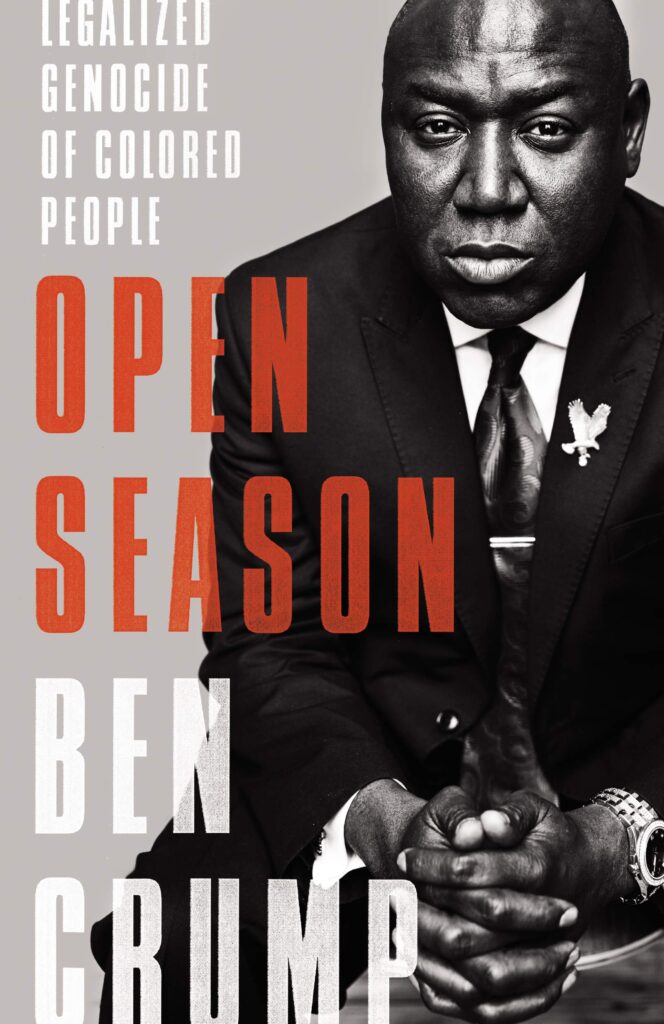

So, when it came time to interview Ben Crump, the lead attorney for Black America, there could be no room for error.

If you want to interview Ben Crump, you had better be ready to strike when the opportunity comes. “Brad, I just landed, I will call you when I get to the car,” Ben Crump said.

Perfect! No, wait, not so perfect. How do you interview the person who might be one of Black America’s last national leaders? Ben Crump was born before the Internet. He was raised at a time when progress meant sacrifice. He doesn’t use today’s playbook of 15-second TikTok reels laced with golden nuggets. He set his standards for himself and America. And for that effort, he has become a superhero for Black justice everywhere.

Benjamin Lloyd Crump was born on October 10, 1969, in Lumberton, North Carolina. He specializes in civil rights and catastrophic personal injury cases such as wrongful death lawsuits. His practice has focused on cases such as Trayvon Martin, Breonna Taylor, Michael Brown, George Floyd, Keenan Anderson, Randy Cox, and Tyre Nichols; people affected by the Flint water crisis, the estate of Henrietta Lacks, and the plaintiffs behind the 2019 Johnson & Johnson baby powder lawsuit alleging the company’s talcum powder product led to ovarian cancer diagnoses. Crump is also the founder of the firm Ben Crump Law of Tallahassee, Florida.

Ben’s office is wherever the next case is. He travels the country tirelessly to represent those who have been wronged by the system. He fights for Blacks in the past, present, and future. He has won cases that no one else can win, and he is determined that if Blacks stay committed, the war for equality can be won.

2024 presents Blacks with a unique situation. The question of where to place the Black vote is getting harder and harder with the available choices.

“There is no silver bullet, we must divorce that from our mind. We must be able to tread water until we can catch a rising tide,” Crump explained. “There are times when we seem to be most marginalized, we cannot lose the war.”

Crump feels like 2024 will not be the end of all elections. He feels like we cannot let the good be the enemy of the perfect.

“We don’t have the perfect candidate this year, so we have to tread water, so we have to get the best we can get and fight for another day,” Crump said.

Crump feels like it doesn’t make a difference who is in office. Blacks must take the lead in determining their fate. Crump believes the fight for Black America starts at the local level. He goes on to define the blueprint for what Blacks need to do to begin to create change at a grassroots level.

“One of the easiest things you can do to help your community is to respond to a summons to become a jury member when the court asks you to,” Crump. “The hardest thing for a Black lawyer to do is to go into the courtroom with a Black client and the only other black thing in the courtroom is the judge’s robe and you expect to get justice.”

Ben wants Blacks to engage in local politics. He wants Blacks to celebrate being on jury duty. He demands that it’s the one way that we know our vote will count. He wants civic organizations and Black businesses to go out and teach the importance of serving on jury duty to ensure that when Blacks are unjustly prosecuted Blacks can be there to make sure their legal battle is fair.

“Blacks sitting on a jury changes the whole dynamic of the courtroom when a fellow Black is being prosecuted,” Crump said. “Once we start winning in the courtroom, we can begin to vote in our local elections to pick the right people to represent our interests.”

Crump feels like voting on a national level is one thing, but picking the right mayor, police chief, fire chief, superintendents of schools, and local judges levels the playing field when it comes to Blacks advancing from the bottom to the top. Local elected officials have far more impact on many Blacks than any other official.

Crump contends that if Blacks got more involved locally then police brutality would be reduced, how local contracts are awarded would be impacted and Blacks would begin to see a difference in the power that is generated from voting.

“Where are they going to build the community center, where are they going to build the courthouse, and where are they going to put affordable housing? All of that is decided at the local level,” Crump said.

Moving from the local voting agenda to fighting to right the harm done to Blacks, Crump has become Black America’s attorney by going after those who commit crimes against Blacks.

One of his recent cases involves the crimes committed against Henrietta Lacks. In 1951, the young mother of five visited The Johns Hopkins Hospital complaining of vaginal bleeding. Upon examination, renowned gynecologist Dr. Howard Jones discovered a large, malignant tumor on her cervix. The illegal collection of Lacks’ cells began what was the first, and, for many years, the only human cell line able to reproduce indefinitely, creating HeLa cells.

The HeLa cells not only remained alive but multiplied at an astonishing rate. Dr. Jones informed his colleagues that his lab had grown the first immortal cell line, and shared samples of HeLa cells with them. Many medical breakthroughs including the polio vaccine, AIDS and cancer treatments, and genome sequencing all came from the endless production of Lacks’ cells.

HeLa cells are also a big moneymaker. Johns Hopkins distributed them for free, but several biotech companies profited from products derived from the cells. Among them is Thermo Fisher, a biotech company with an annual revenue of over $40 billion.

When Crump was approached to take the case, he knew he had an uphill battle to right the wrong that was committed against Lacks. Her cancer was never treated, and she was allowed to die, poor and broken, but her cells went on to live and change the way medicine is researched. Crump knew something had to be done.

“Black people get sick and tired of hearing about how we were used and sacrificed by the medical community. When the case was presented to me, I knew that I had to do something to help this family who got nothing while big pharmaceutical companies, even today, are making billions off her cell production,” Crump said.

That statute of limitations to go after any company that profited from Lacks’ cells ran out four years after the illegal donation. The legal community thought Crump was wasting his time by taking on the case of winning some revenue for Lacks’ family.

He went to court and didn’t argue the fact that in 1951 Lacks’ rights were violated. The statute blocked that argument. Crump argued that the family of Lacks should profit from the current cell production of Lacks. The judge agreed and the family settled with the first pharmaceutical company for an undisclosed amount, bringing some closure to the family, who up to his point hadn’t gotten anything from the discovery of her cell reproduction.

The victory for the Lacks family is just one of many that Crump has won for families across America. Today, Crump travels the country, like a superhero, fighting for justice for those who cannot fight for themselves.

Crump is the definition of a hero: A morally righteous hero who possesses extraordinary abilities or supernatural powers and uses them to fight evil.

He may not wear a cape, and he may not be able to fly, but when his plane lands, he plugs in, focuses, and devotes his time to protecting those who need it the most. CODE M celebrates Ben Crump during Black History Month for his bravery and his efforts to make a difference in his own life and for those lives he gets a chance to touch.